“Kamikaze,” a once-nightmare weapon for America in World War II, by destroying Pearl Harbor and badly damaging the American navy, came once again, but this time it came for the whole American economy, and in an intangible form, and popularly known as “American debt” in the financial world, does this instrument result in dawn of a new Imperial Japan, or does another “Fat Man” and “Little Boy” await?

Kanban Card: Japanese Economy

Following its surrender in WWII, Japan restructured its economy by blending domestic discipline with Western capitalism under the US “Nuclear Umbrella.” The nation dismantled its military and broke up “zaibatsu” conglomerates, shifting industrial focus from military hardware to commercial goods, depending mainly on the American economy. The 1950 Korean War presented a significant opportunity, generating a substantial logistical demand that infused capital and stimulated industrial growth.

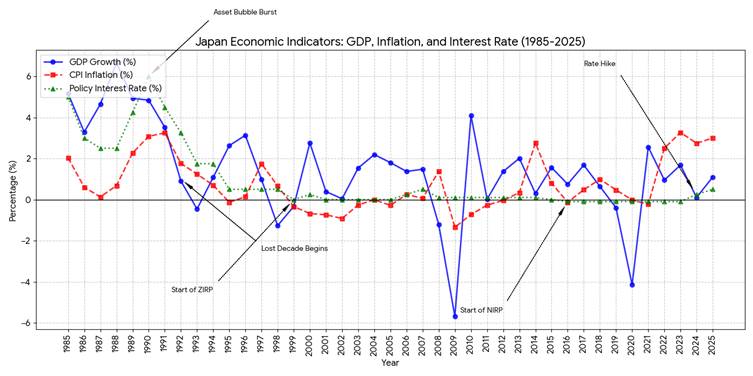

From 1950 to 1970, Japan witnessed rapid annual growth exceeding 10%, which was way ahead of the American economy’s growth rate. Innovations like Kaizen and lean manufacturing revolutionized production quality, crowning Japan the world’s second-largest economy by the late 1980s. However, this ascent halted in 1990 when the asset bubble burst, triggering the “Lost Decade.” The economy suffered hyper-deflation and massive non-performing assets; revival attempts like “Abenomics” yielded limited results.

As of 2025, Japan stands as the world’s fourth-largest economy. While the service sector and high-tech manufacturing remain strong, economic indicators are stagnant, with GDP growth hovering between 0.5% and 1.5% and low inflation. Though supported by government stimulus, the economy now navigates the dual pressures of global trade uncertainty and the demographic challenges of an aging society.

US Debt: An Economic Orichalcum Shield

From barter trade to currency system, whenever this world feels it is going to face some kind of economic uncertainty, it seeks the help of an immortal investment tool, which is ‘gold.’ Gold, from ancient times, holds its importance as the safest asset for investment, even when there are various other investments. Gold’s shine never faded in the investment world, but with time, other companions had become partners of the king in yellow, like petroleum and fixed deposits, but the most exceptional one was ‘US debt.’

The paper, which says it is a bond issued by the American government, came into existence first in the 1770s, and it has saved America and the American economy time to time again with different names in disguise, like revolutionary bonds, liberty bonds, war bonds, etc. The bonds over time have had to pay a yield in double digits and now have a yield of nearby of around 3.5%, which shows the result of the clear dominance of the American economy built up in these past centuries.

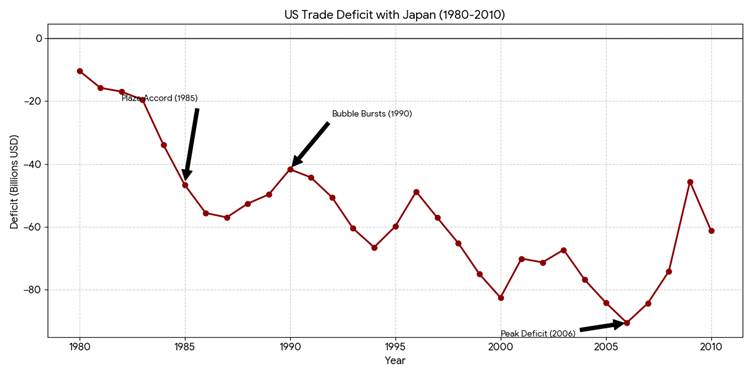

Backstory: Japan Rom-Com with US Debt

The trade after the Korean War between America and Japan was one-sided; the katana weighed heavier than the M-16, at least in terms of trade surplus. For the last 50 years, the American economy has faced a trade deficit with Japan in terms of goods trading, and the goods that are greatly flooding the American market are mainly automobiles, engineering products, consumer electronics, and heavy machinery, which can be easily identified as the backbone of the American manufacturing sector. These locally manufactured products generate huge economic output for the American economy, and this act will surely be unacceptable to the US. Japan also does not want a non-cooperative relationship with America, so it found a middle path to address this trade imbalance, which eventually ends up in Washington, DC’s pocket: buying US bonds and investing in the American economy to counter the trade imbalance on Japan’s side.

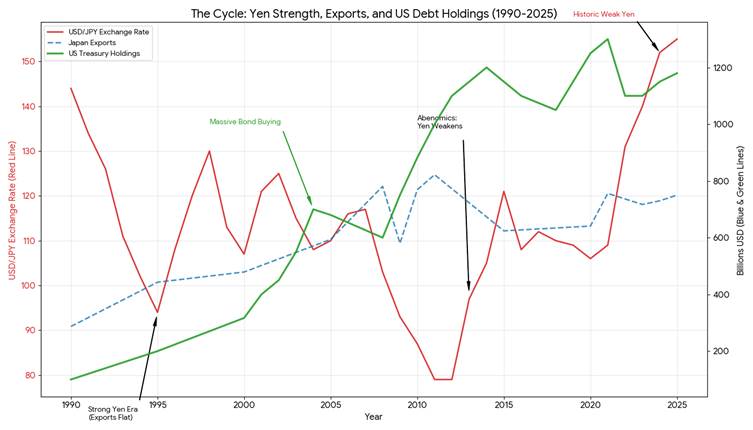

Trade imbalance was not only the sole reason why Japan invested in the American economy and bonds, there was also another benefit, which was the ‘devaluation’ of currency, the exporter exports goods from Japan to US and receive payment in US dollar and exporters convert this US dollars into Yen and because there is an deficit in trade demand for yen compare to dollar is more which results in strengthening of yen compare to dollar, strengthening of Japanese means exporter will get less yen compare to last time sales of same value because yen has strengthened itself but in devaluated situation exporter will get same value of yen compare to last time sales.

How is this Kamikaze Isekai in the American economy?

Japan, for very serious reasons, bought up the American debt, which supported the American economy to its greatest length, but here is the point where the problem arose for America, which can be simply stated in a simple question that “What if Japan sold all of the bonds?”.

Japan will not just wake up and think one day, “today’s weather seems perfect for a tea ceremony, let’s crash the American economy.” Japan will surely need a very peculiar reason to drop this Kamikaze on the American economy, like to defend its currency from falling, or to have access to dollars on immediate terms. It will then dump the bonds on the market, and if any situation like this takes place, then the effect will be catastrophic for the US.

Effect on the US: –

A massive dump of U.S. bonds by Japan would send shockwaves through the American economy, especially for everyday citizens. Suddenly flooding the market with bonds while demand remains the same or grows only slightly, would definitely push interest rates sharply upward. If rates were near 3.6% before the dump, they could easily shoot up to 8% afterward. This would make banks rush toward the high returns in the bond market, leaving far less cash available for commercial loans. As a result, cash flow in the American economy would tighten, and consumers would struggle to secure loans for homes, cars, or other big purchases.

Producers would also be facing a credit crunch. Without access to affordable financing or bank’s special credit facilities, companies would find it difficult to sustain or maintain production levels. This would surely slow down supply chains and push up the cost of raw materials, further straining the economy.

The dollar would also be devalued. By selling $1 trillion worth of U.S. debt and converting it into yen, Japan would surely create a surge in the dollar’s supply artificially, pushing its value down relative to other currencies. A weaker dollar would make imports cheaper and reduce the competitiveness of American exports.

In addition, a sudden sell-off could trigger a wave of frequent inflation that would take a long time to cool off. The Federal Reserve would most likely be forced to step in as the “lender of last resort,” by buying the dumped bonds aggressively, which is also known as quantitative easing. While this might stabilize debt and the exchange market for the short term, printing large amounts of money would eventually increase the money supply and fuel long-term inflation worries, potentially undermining trust in the U.S. financial system.

Effect on Japan: –

If Japan suddenly tried to sell $1 trillion worth of U.S. Treasuries, it would run into a basic problem that there simply aren’t enough buyers willing to take that much at today’s price. To move the bonds quickly from kitty to market, Japan would have to offer them at a hefty discount, and that kind of panic selling would push U.S. interest rates up. Even a modest 2% jump could wipe out 15% to 20% of the bonds’ value. By the time the dust settled, Japan might get back only $700 to $800 billion, meaning $200 to $300 billion of its own wealth would just disappear. In short, trying to cash out would hurt Japan far more than anyone else.

The moment Japan starts selling the bonds, the dollar would fall, and the yen would surge. At first, they might convert a few billion at the prevailing exchange rate, but with each additional sale, the dollar would weaken further. By the time they reach the end of the conversion, the remaining dollars could be worth far less, which can also be termed as “melting” in value as they trade them. In the process, Japan would lose a huge chunk of its national asset simply because the act of converting such a massive amount would destroy the dollar’s value against the yen.

Yen would shoot up in value, making Japanese products far more expensive overseas. A car like a $25,000 Toyota Camry in the U.S. could suddenly jump to $40,000 simply because of the hyper fluctuation in the exchange rate. At those prices, American and European buyers would walk away, and Japan’s export-driven companies would see sales crash almost overnight. As profits disappear, the economy would slow down, layoffs would rise, and many firms could even face bankruptcy. In short, a super-strong yen wouldn’t make Japan richer instead, it would choke the very industries that keep its economy running.

Where is the Captain America Shield for this Kamikaze?

The “Captain America Shield” protecting both the American economy from an economic Kamikaze from Japan isn’t made of Vibranium, but it’s built from geopolitical and geo-economic co-dependency and mutually assured financial destruction. Japan relies heavily on the U.S. “nuclear umbrella” for its external security, especially with time-to-time rising tensions from China and North Korea. Crashing the U.S. economy would mean crippling the very protector that keeps Japan safe.

Then comes the “Customer-is-King” reality check. The American economy is Japan’s biggest buyer of cars, electronics, and high-tech goods. If Japan somehow deliberately triggered a financial meltdown by dumping U.S. debt, it wouldn’t just destroy an investment; it would destroy its biggest customer. The scenario would be like a shopkeeper burning down the homes of all his buyers just to prove a point.

That’s why this economic “Kamikaze” will never take off, at least under normal circumstances. Both nations understand the consequences, and neither side has unusual circumstances. Their relationship has evolved from wartime enemies into an uneasy but deeply bilateral economic partnership.

So, will there be another “Fat Man”? The answer is mostly No. Instead of a dramatic financial explosion, Japan will likely trim its U.S. debt holdings slowly and quietly. Not a shockwave, which can just make some gradual adjustment in a world moving toward multipolar balance.